26.PHEW

A marathon is earned suffering. You work very hard for 18 weeks, running 400-odd miles all in, just to get to the point where you're able to run long enough to use up all the stores of glycogen in your muscles. That sounds fun, right? And boom, you're done.

(I'm not talking to you, Dean Karnazes/Marshall Ulrich/Todd Jennings, crazy long-distances runner types. I'm talking to the over-3:30 set and slower...like Paul Ryan slow. Like me.)

So, yeah, run through your glycogen and get a space blanket. Sure. Except that most people run through those stored carbohydrates around mile 18, or 20, or 22.

Which means you've got 8.2 or 6.2 or 4.2 miles to go. And it's those miles that are your reward. They fucking hurt! In a good way! You have to run them with your brain! And while you're running them (hahaha, "running" them, yeah right), you're thinking things like "why why why why step step step step step why why why why c'mON mutherfukker" mostly, but also, if you're like me, you're reflecting on the end of Infinite Jest (and, sadly, you take no pleasure in the fact that you read it AGES ago and the people around you probably didn't and are philistines), the part where Gately's in the hospital and seeing the D.A. sitting outside and he's enduring each millisecond knowing that the pain contained in a millisecond is finite and he's continuing and continuing and continuing and continuing, etc. This reflection is made less enjoyable, if you're like me, by the constant presence over your left shoulder of a possibly hallucinatory prosecuting attorney in a fedora running effortlessly and taunting you and calling you fattie, but that's just me OR IS IT. You might also, as I did this past spring, reflect on the pain that it was to be David Foster Wallace, and how tough life must have been for that poor guy, and how brave he seems in retrospect to have been in the face of such crushing depression, and how lovely some of his thinking and phrasing and structure and (I'm not going to footnote this) convoluted sentences were. And you might start to mantrafy the words "this is water this is water this is water."

I've run four marathons, the most recent one this past spring after a six-year hiatus (child #2 really puts a dent in your whole thing). And it was during this one that it struck me that if I hadn't trained as hard as I had, I would not have earned the pain of those last four miles. I would not have had the opportunity to find a limit for myself, lean into it, push against it, and shove it back—maybe not as hard as I'd like, but still—shove it back for another 44 minutes after I reached it, until I decided to stop. A marathon gives you a chance, within an otherwise normal, even comfortable, life, to be told NO by the universe and to answer back 'FRAID SO.

They say you hit a wall in the marathon, and you do. But what they don't usually tell you is that you can choose to grab hold of the wall—it's about seven feet tall and eight feet wide, made of stacked 4x4s— hoist it painfully over your head, stagger to the finish line under its weight, then throw it onto the ground flat and stand on it while they take your picture.

If you don't believe me, take a look at those post-finish-line photos. Everyone in them is actually about four inches taller.

•

(I'm not talking to you, Dean Karnazes/Marshall Ulrich/Todd Jennings, crazy long-distances runner types. I'm talking to the over-3:30 set and slower...like Paul Ryan slow. Like me.)

So, yeah, run through your glycogen and get a space blanket. Sure. Except that most people run through those stored carbohydrates around mile 18, or 20, or 22.

Which means you've got 8.2 or 6.2 or 4.2 miles to go. And it's those miles that are your reward. They fucking hurt! In a good way! You have to run them with your brain! And while you're running them (hahaha, "running" them, yeah right), you're thinking things like "why why why why step step step step step why why why why c'mON mutherfukker" mostly, but also, if you're like me, you're reflecting on the end of Infinite Jest (and, sadly, you take no pleasure in the fact that you read it AGES ago and the people around you probably didn't and are philistines), the part where Gately's in the hospital and seeing the D.A. sitting outside and he's enduring each millisecond knowing that the pain contained in a millisecond is finite and he's continuing and continuing and continuing and continuing, etc. This reflection is made less enjoyable, if you're like me, by the constant presence over your left shoulder of a possibly hallucinatory prosecuting attorney in a fedora running effortlessly and taunting you and calling you fattie, but that's just me OR IS IT. You might also, as I did this past spring, reflect on the pain that it was to be David Foster Wallace, and how tough life must have been for that poor guy, and how brave he seems in retrospect to have been in the face of such crushing depression, and how lovely some of his thinking and phrasing and structure and (I'm not going to footnote this) convoluted sentences were. And you might start to mantrafy the words "this is water this is water this is water."

I've run four marathons, the most recent one this past spring after a six-year hiatus (child #2 really puts a dent in your whole thing). And it was during this one that it struck me that if I hadn't trained as hard as I had, I would not have earned the pain of those last four miles. I would not have had the opportunity to find a limit for myself, lean into it, push against it, and shove it back—maybe not as hard as I'd like, but still—shove it back for another 44 minutes after I reached it, until I decided to stop. A marathon gives you a chance, within an otherwise normal, even comfortable, life, to be told NO by the universe and to answer back 'FRAID SO.

They say you hit a wall in the marathon, and you do. But what they don't usually tell you is that you can choose to grab hold of the wall—it's about seven feet tall and eight feet wide, made of stacked 4x4s— hoist it painfully over your head, stagger to the finish line under its weight, then throw it onto the ground flat and stand on it while they take your picture.

If you don't believe me, take a look at those post-finish-line photos. Everyone in them is actually about four inches taller.

•

Saturday

I had the pleasure of going to a party where a bunch of people said really nice things about one of my recent social media status updates. It might be the work I'm most proud of this year so far.

•

•

Life is Like a Game of Wack-a-Mole

Lives average out, right? If you're a mousy office drone who works endless hours at small, thankless tasks laden with nearly pointless detail, you're much more likely to unleash your caged Mongol warrior on the weekends (there's that bit in Hitchhiker's Guide where the town councilman's genes cry out to him), or if you're a serial entrepreneur with a family to feed who nevertheless starts up more and more outlandish enterprises that have no chance of succeeding, defying the odds, spitting in the face of potential starvation and irrelevance, you're also a germophobe who can't use a public restroom.

At the post office, when I worked there one summer, lots of the guys were veterans, and they liked to calm one another down, or pretend to calm one another down, with the military advice to "maintain an even strain." (I'm pretty sure this has its roots in Army training films on lifting heavy objects -- I had lots of training on lifting heavy objects that summer.) They'd say it like "maintaaaain an even strain." That sounds right, right? You do each thing with the right level of intensity, you make sure your bravery is just foolhardy enough and you make sure your fears are grounded in reality. You inject creativity into your boring office job and you go dancing on the weekend instead of riding a bison down main street and smashing into the sushi place.

That kind of balance is unsustainable, of course (and, let's face it, boring), which is why those post office guys used to have to keep saying it to each other all day. Your energy level shifts, you're wired to do certain things a certain way at certain times. Not enough oatmeal one week, you're going to flush all your Ideas files down the can; too much and you start singing really loud in the TSA line.

So, knowing that there are going to be highs and lows, I recommend trying to average out individual days. Just spend half of every minute screaming and the other half laughing. Average!

•

At the post office, when I worked there one summer, lots of the guys were veterans, and they liked to calm one another down, or pretend to calm one another down, with the military advice to "maintain an even strain." (I'm pretty sure this has its roots in Army training films on lifting heavy objects -- I had lots of training on lifting heavy objects that summer.) They'd say it like "maintaaaain an even strain." That sounds right, right? You do each thing with the right level of intensity, you make sure your bravery is just foolhardy enough and you make sure your fears are grounded in reality. You inject creativity into your boring office job and you go dancing on the weekend instead of riding a bison down main street and smashing into the sushi place.

That kind of balance is unsustainable, of course (and, let's face it, boring), which is why those post office guys used to have to keep saying it to each other all day. Your energy level shifts, you're wired to do certain things a certain way at certain times. Not enough oatmeal one week, you're going to flush all your Ideas files down the can; too much and you start singing really loud in the TSA line.

So, knowing that there are going to be highs and lows, I recommend trying to average out individual days. Just spend half of every minute screaming and the other half laughing. Average!

•

"Have a seat," they said. I sat.

Why NaBloPoMoWriMo?

I am blogging an average of once per day this month because I'm supposed to be finishing (for the third time) the novel I started during NaNoWriMo in 2009 and this seemed like the best way to procrastinate.

•

•

Update: Nothing Has Changed

Fiveish years ago I wrote about a couple of developments underway in the woodlands surrounding my town. Neither has been built yet; one is still under way and the other is held up in various zoning wrangles. Thankfully. It takes sixty years to grow the woods, and just a month to cut them down—so it's probably worth an extra year or two to be sure you want to do that, before you do that.

In any case, someone stopped by where I was sitting today and asked if I had an opinion on that one, the tied up one, and I said oh sure, and I said, actually, here.

•

In any case, someone stopped by where I was sitting today and asked if I had an opinion on that one, the tied up one, and I said oh sure, and I said, actually, here.

•

Three Millimeters is Enough

Took me four hours and forty minutes to get home last night. Three millimeters of ice had coated the roads, and the bottom of every hill held a drift of cars that reminded me of the boats from the marina after Hurricane Sandy, all piled up together. I should have been using my phone to blog while parked on Route 9 in the hills up behind Cold Spring, wind whipping the trees and light sleet falling, but instead I listened to the radio, wondered about the identity of the people in the cars ahead of me and behind me, texted the friends who had picked up the kids, reflected on how every moment of the past had led up to that dark night and the high-pitched zzzzzip of someone's tires looking for purchase, the ticking of the sleet on the windshield.

•

•

With Daylight Savings Like This

STS-133

I wrote this in February 2011. -- BB

Just inshore from the Indian River in Titusville, Florida, there is a pool of water set off from the estuary by a berm and a metal baffle, and in this pool there is an alligator.

Titusville is widely known as the third-best place from which to watch the space shuttle launch from the Kennedy Space Center on Cape Canaveral, twelve miles east, across the wide expanse of the northern Indian River. The first two best places are both attached to the space center, and you need tickets to watch the launches from there. They’re about three miles closer.

The shuttle launches from launchpad 39A, or at least the Discovery launched from there on February 24, 2011. You can see 39A from anyplace along the western shore of the river, which is a developed strip on the shoulder of US1 running north-south through town. At the northern end of Titusville, just where the causeway to the space center comes to land, is Spaceview Park. Spaceview Park comes recommended because there’s a PA system counting down the launch, and a Jumbotron showing a closeup view of the spacecraft as it takes off. But farther south there are some open areas that work okay for peering across the water through binoculars. Thousands of people come to town to set up their tripods and stake out their places, hours before liftoff.

The alligator is medium-sized. Not a great brooding veteran nor a hatchling, it looks to be about five to six feet long, and on the morning of the launch it lay still, close to the riverward side of the pool, floating perpendicular to the coast, looking almost pointedly away from the launch site.

He or she may have had reason to be piqued. The February 24, 2011 launch of Discovery, to deliver a structural element to the International Space Station, is to be the penultimate launch of the Shuttle. The fleet is old, and expensive, and the hope is that private industry will step in to provide some of the expensive answers to space R&D that the government is increasingly wary of financing.

For the gator, this spells trouble. For strewn around its watery home are the possible remains of meals. There’s a McDonald’s about fifty yards away, a hot dog place across US1, and beside a marquee reading “GO DISCOVERY / ICE COLD MARGARITAS”—next to a branch of the Kennedy Space Center Federal Credit Union—is a palatial Tex-Mex place called El Leoncita. Wrappers and cups litter the shoreline of the alligator’s fenced-off enclosure. The alligator, I suspect, eats well when shuttles go up.

Indeed, it seems an unlikely place to find a reptile of this size. There is little about the immediate environment to suggest any organic sustenance for our friend. There don’t seem to be any fresh waterways nearby (the Indian River is an estuary, and salt). There can’t be too many fish in the little pond, certainly, and the gator is so obvious within its confines that it’s hard to imagine unwary wading birds stopping in.

More likely it is the by-blow of the shuttle program and its legions of fans arriving to set up lawn chairs along the gator’s fence that keep the animal fed. A few chicken nuggets, a beef patty, the end of a burrito, Mom’s fried chicken—the tourists come, and, intentionally or not, the detritus of their visits winds up fair game. Otherwise, what does it eat? Rats? Maybe.

Probably, for the gator, the end of the shuttle program means hunger or departure. It’s unlikely that Titusville’s residents—proprietors of the Space Shuttle Car Wash, for instance—will think to spare a Big Mac for the green guy in his pond up the road. He or she is in an out of the way spot, near a public park, but there’s nothing picturesque about it (partly on account of the garbage, and the fence). Its primary advantage is its proximity to the best views of 39A. And the government can’t keep pushing millions at the shuttle program indefinitely. There’s no plan or stomach to build the next generation vehicle. Most signs point to future ships becoming expensive tools, rather than romantic engines of discovery. Robotics. Small scale machines remotely controlled, performing assembly and repairs under orders from Houston. Hard to imagine crowds like this coming out to watch those smaller, less soul-stirring gouts of flame across the lapping waves.

But that’s tomorrow. On this February, our attention is drawn by the countdown, and the puff of smoke across the water, and the cheers of the crowds as a white-gold dragon’s-scale of flame rises into the sky and a nearly-divine delayed thunder rolls across the miles. A trail of expanding white thrusts upward, piercing a thin layer of clouds, emerging again to take the heavens. A star remains for a time, fading off into space, into its work beyond the blue dome that remains. We shuffle back to the car, wrapped in the glory of the moment, rehashing and stopping occasionally to look back and up at the dissipating exhaust.

Later, we get caught in the roach motel of traffic from all three prime viewing spots, all converging on a single interstate entrance ramp which is predictably impassable. It’s late, we’re hungry, and there is a bright clot of chain restaurants and hotels surrounding the traffic-filled arena. So we stay a little longer to buy cheeseburgers and coffee by the highway out of town. Later, fed but still stymied by the non-flow of cars onto I-95, we drive back into Titusville and head south on a nearly deserted US1.

Here, on the river side of town, and in the endless towns along this highway on this summery February night, every strip mall boasts a bail bondsman and a pawn shop. But for now, and for another month, the shuttle swings overhead.

•

Just inshore from the Indian River in Titusville, Florida, there is a pool of water set off from the estuary by a berm and a metal baffle, and in this pool there is an alligator.

Titusville is widely known as the third-best place from which to watch the space shuttle launch from the Kennedy Space Center on Cape Canaveral, twelve miles east, across the wide expanse of the northern Indian River. The first two best places are both attached to the space center, and you need tickets to watch the launches from there. They’re about three miles closer.

The shuttle launches from launchpad 39A, or at least the Discovery launched from there on February 24, 2011. You can see 39A from anyplace along the western shore of the river, which is a developed strip on the shoulder of US1 running north-south through town. At the northern end of Titusville, just where the causeway to the space center comes to land, is Spaceview Park. Spaceview Park comes recommended because there’s a PA system counting down the launch, and a Jumbotron showing a closeup view of the spacecraft as it takes off. But farther south there are some open areas that work okay for peering across the water through binoculars. Thousands of people come to town to set up their tripods and stake out their places, hours before liftoff.

The alligator is medium-sized. Not a great brooding veteran nor a hatchling, it looks to be about five to six feet long, and on the morning of the launch it lay still, close to the riverward side of the pool, floating perpendicular to the coast, looking almost pointedly away from the launch site.

He or she may have had reason to be piqued. The February 24, 2011 launch of Discovery, to deliver a structural element to the International Space Station, is to be the penultimate launch of the Shuttle. The fleet is old, and expensive, and the hope is that private industry will step in to provide some of the expensive answers to space R&D that the government is increasingly wary of financing.

For the gator, this spells trouble. For strewn around its watery home are the possible remains of meals. There’s a McDonald’s about fifty yards away, a hot dog place across US1, and beside a marquee reading “GO DISCOVERY / ICE COLD MARGARITAS”—next to a branch of the Kennedy Space Center Federal Credit Union—is a palatial Tex-Mex place called El Leoncita. Wrappers and cups litter the shoreline of the alligator’s fenced-off enclosure. The alligator, I suspect, eats well when shuttles go up.

Indeed, it seems an unlikely place to find a reptile of this size. There is little about the immediate environment to suggest any organic sustenance for our friend. There don’t seem to be any fresh waterways nearby (the Indian River is an estuary, and salt). There can’t be too many fish in the little pond, certainly, and the gator is so obvious within its confines that it’s hard to imagine unwary wading birds stopping in.

More likely it is the by-blow of the shuttle program and its legions of fans arriving to set up lawn chairs along the gator’s fence that keep the animal fed. A few chicken nuggets, a beef patty, the end of a burrito, Mom’s fried chicken—the tourists come, and, intentionally or not, the detritus of their visits winds up fair game. Otherwise, what does it eat? Rats? Maybe.

Probably, for the gator, the end of the shuttle program means hunger or departure. It’s unlikely that Titusville’s residents—proprietors of the Space Shuttle Car Wash, for instance—will think to spare a Big Mac for the green guy in his pond up the road. He or she is in an out of the way spot, near a public park, but there’s nothing picturesque about it (partly on account of the garbage, and the fence). Its primary advantage is its proximity to the best views of 39A. And the government can’t keep pushing millions at the shuttle program indefinitely. There’s no plan or stomach to build the next generation vehicle. Most signs point to future ships becoming expensive tools, rather than romantic engines of discovery. Robotics. Small scale machines remotely controlled, performing assembly and repairs under orders from Houston. Hard to imagine crowds like this coming out to watch those smaller, less soul-stirring gouts of flame across the lapping waves.

But that’s tomorrow. On this February, our attention is drawn by the countdown, and the puff of smoke across the water, and the cheers of the crowds as a white-gold dragon’s-scale of flame rises into the sky and a nearly-divine delayed thunder rolls across the miles. A trail of expanding white thrusts upward, piercing a thin layer of clouds, emerging again to take the heavens. A star remains for a time, fading off into space, into its work beyond the blue dome that remains. We shuffle back to the car, wrapped in the glory of the moment, rehashing and stopping occasionally to look back and up at the dissipating exhaust.

Later, we get caught in the roach motel of traffic from all three prime viewing spots, all converging on a single interstate entrance ramp which is predictably impassable. It’s late, we’re hungry, and there is a bright clot of chain restaurants and hotels surrounding the traffic-filled arena. So we stay a little longer to buy cheeseburgers and coffee by the highway out of town. Later, fed but still stymied by the non-flow of cars onto I-95, we drive back into Titusville and head south on a nearly deserted US1.

Here, on the river side of town, and in the endless towns along this highway on this summery February night, every strip mall boasts a bail bondsman and a pawn shop. But for now, and for another month, the shuttle swings overhead.

•

Don't Sweat the Small Stuff that Dreams Are Made Of

Not far from my house is a coffee shop. Once a month, I host a karaoke night there. In exchange the owners give me tokens for free coffee, plus beers during the evening itself. My "hosting" duties include kicking things off with peculiar renditions of popular songs, and making puns between numbers by other singers.

If you're a married man in his 40s with kids, hosting karaoke in your neighborhood is among the most fun things you can do on a Saturday night. That sentence wants to sound pathetic, but it just can't. It's funner than movies. It's funner than bars. It's funner than the opera. It might not be funner than going to see live music by a great band, but it's closer and, instead of costing a boatload of money for a sitter and transportation and tickets and a kid-sized plastic cup of warm ginger ale with a splash of Old Grandad in, it pays you beer and coffee.

And it's good to hold the mic.

Small entertainments pack as much emotional grandeur as the big things; on some Saturdays you just need enough to cement social ties, put a pleasant tune in your head, give you a chuckle, let you show off a little, picture your life a little bigger. It doesn't all have to be big. It doesn't have to be grand. Where I live there are landscapes and monumental sculpture and the river to deliver grandeur — and not too far away is the glow of the city, to which we've been known to repair for big kicks. But most Saturdays, I only need so much. And the backyard delivers.

Tonight a guy asked to sing this song a capella. Nailed it.

Superstar.

•

If you're a married man in his 40s with kids, hosting karaoke in your neighborhood is among the most fun things you can do on a Saturday night. That sentence wants to sound pathetic, but it just can't. It's funner than movies. It's funner than bars. It's funner than the opera. It might not be funner than going to see live music by a great band, but it's closer and, instead of costing a boatload of money for a sitter and transportation and tickets and a kid-sized plastic cup of warm ginger ale with a splash of Old Grandad in, it pays you beer and coffee.

And it's good to hold the mic.

Small entertainments pack as much emotional grandeur as the big things; on some Saturdays you just need enough to cement social ties, put a pleasant tune in your head, give you a chuckle, let you show off a little, picture your life a little bigger. It doesn't all have to be big. It doesn't have to be grand. Where I live there are landscapes and monumental sculpture and the river to deliver grandeur — and not too far away is the glow of the city, to which we've been known to repair for big kicks. But most Saturdays, I only need so much. And the backyard delivers.

Tonight a guy asked to sing this song a capella. Nailed it.

Superstar.

•

Move

I haven't seen the destruction in New York firsthand. My town was more or less spared by Hurricane Sandy. Trees and power lines down, power out for a couple of days, no major flooding.

But I lived in New York City for eight years, my sisters and cousins and friends still do, and I've been talking with my people.

They say that the New York City Marathon is scheduled to go on this Sunday, less than a week after lives and neighborhoods were destroyed by the storm. The power is still out. Transportation is a debacle. There's wreckage in places that hasn't even been touched yet. The race is set to go, and apparently people are angry.

The race ought to go on.

In 2001 I recall being angry. Vindictive. Scared. I thought maybe the marathon would devalue my grief. That a celebration of life so soon after death would be disloyal to the dead. That I might forget, and we were very clearly told to NEVER FORGET.

But I went out to cheer for the runners, cheer for the city, cheer for my living, cheering friends around me eating bagels. In 2003, completely renewed -- a father, a runner, no longer a New Yorker -- I ran that race. I ran it again a couple of years later. Forget? Hardly.

The New York City Marathon is an annual heartbeat in a city that's all heart. If you're angry that the marathon is going on, remember what got you angry. That storm was unfair.

And one day taken from a cleanup and rebuilding that is going to take years is a small price, on top of the price already paid. More important, the marathon is an investment of spirit in a place that needs it. This marathon will be like the news of V-day. It will be like the end of the '68 blackout. It will be like -- well, it will be like the New York City Marathon in 2001.

This isn't an abstract thing, here. The marathon is a real thing. It saves lives. It redirects energy. The city is at a standstill? Not if you let tens of thousands of people run through it. You can't get anywhere? Yes you can. Use your feet. The power is out? The power is right there in front of you, taking in air and turning it into kinetic energy. You're going to tell the world that storm, blackout, and tragedy can shut New York down? You're going to tell people that the place they travel in droves to see is not as mighty as they think it is? New Yorkers: you live in the center of the universe. Light it up.

If you're angry, and you're sad, and you're frightened, make your way to the course on Sunday and let your emotions go. Cheer. Cry. Hand someone an orange. Let the brave men and women running that race -- many of whom also lost much during this storm -- let them help you remember to be alive.

•

They say that the New York City Marathon is scheduled to go on this Sunday, less than a week after lives and neighborhoods were destroyed by the storm. The power is still out. Transportation is a debacle. There's wreckage in places that hasn't even been touched yet. The race is set to go, and apparently people are angry.

The race ought to go on.

In 2001 I recall being angry. Vindictive. Scared. I thought maybe the marathon would devalue my grief. That a celebration of life so soon after death would be disloyal to the dead. That I might forget, and we were very clearly told to NEVER FORGET.

But I went out to cheer for the runners, cheer for the city, cheer for my living, cheering friends around me eating bagels. In 2003, completely renewed -- a father, a runner, no longer a New Yorker -- I ran that race. I ran it again a couple of years later. Forget? Hardly.

The New York City Marathon is an annual heartbeat in a city that's all heart. If you're angry that the marathon is going on, remember what got you angry. That storm was unfair.

And one day taken from a cleanup and rebuilding that is going to take years is a small price, on top of the price already paid. More important, the marathon is an investment of spirit in a place that needs it. This marathon will be like the news of V-day. It will be like the end of the '68 blackout. It will be like -- well, it will be like the New York City Marathon in 2001.

This isn't an abstract thing, here. The marathon is a real thing. It saves lives. It redirects energy. The city is at a standstill? Not if you let tens of thousands of people run through it. You can't get anywhere? Yes you can. Use your feet. The power is out? The power is right there in front of you, taking in air and turning it into kinetic energy. You're going to tell the world that storm, blackout, and tragedy can shut New York down? You're going to tell people that the place they travel in droves to see is not as mighty as they think it is? New Yorkers: you live in the center of the universe. Light it up.

If you're angry, and you're sad, and you're frightened, make your way to the course on Sunday and let your emotions go. Cheer. Cry. Hand someone an orange. Let the brave men and women running that race -- many of whom also lost much during this storm -- let them help you remember to be alive.

•

Something Stirring

Harvesting

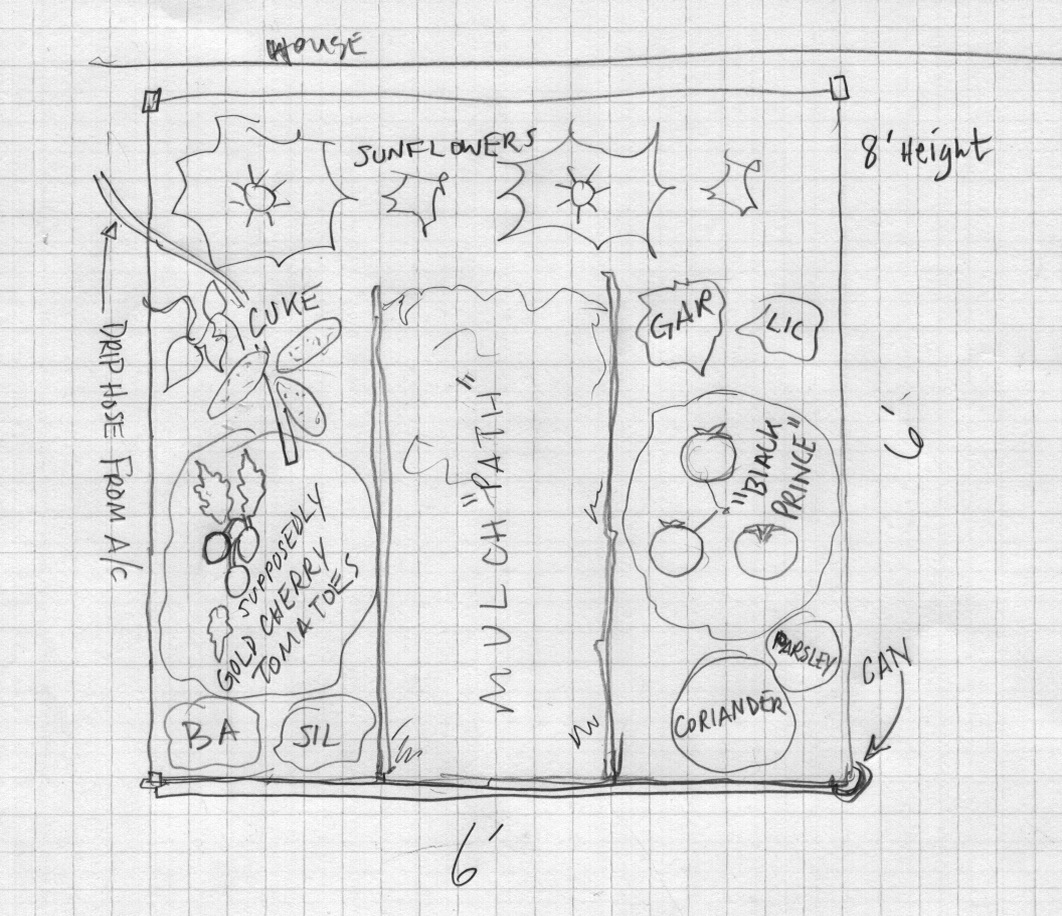

A year and a half in the garden, and the harvest is modest but significant. I'm now blogging for our local food co-op, bringing the same mix of addlepated hilarity, aw-shucks sincerity, whimsical tomfoolery, plaid demonstrativeness, and pithy whining that you're used to from Exurbitude. I hope you'll stop in.

•

Laying this Hammer Down

My neighbor Pete Seeger once told the musician Josh Ritter "the most important thing you could ever do is to choose a place and dig in."

I've done the first part, but I've fallen behind on the second part. So I'm taking a break of indeterminate length from Exurbitude.

This past weekend, I went away to San Francisco to see how much farther blogging could take me, and while I was gone the garden went batshit crazy. The tomatoes got heavy with fruit, reared up and fell over, deer ate practically all the leaves off the pumpkins, and the cilantro started to self-sow. My kids got larger. The tolerant, generous, dedicated woman who loves me went to the meeting for the new food co-op, and she introduced the clothesline I put in last week to its first set of fresh laundry. She sent me a picture of the sun shining on our lives.

Of all the things I learned in San Francisco, the one that applies here is that blogging differs from writing, which I’ve been doing all along. Blogging demands more, and writing is just the centerpiece to a world of commenting, flickring, twittering, emailing…what we call building virtual community.

I’ve found incredible people in that community (see partial list at left). And thank you all who are reading this for being part of it, and for your indulgence. But it also turns out that I live in a community. It’s made up of people I like and don’t like, resemble and don’t resemble, agree and disagree with, and whom I can look in the eye and argue with at a meeting, but keep it civil because later I’ll run into them at the convenience store. I haven’t been engaging my community properly, either.

At the BlogHer conference last weekend, there was a panel on following your passion in which everyone agreed that the lamest Internet thing you could do was to raise up your fist and walk off the blogging stage with a grand, gestural post. Eye roll. So I'm not doing that; I don't swear to be gone for all time. My five year old — who found his first loose tooth tonight — says things like "forever." I don't.

Ahhhh, who am I kidding? The grand gesture ROCKS. Anyone needs me, I'll be tending the garden.

•

I've done the first part, but I've fallen behind on the second part. So I'm taking a break of indeterminate length from Exurbitude.

This past weekend, I went away to San Francisco to see how much farther blogging could take me, and while I was gone the garden went batshit crazy. The tomatoes got heavy with fruit, reared up and fell over, deer ate practically all the leaves off the pumpkins, and the cilantro started to self-sow. My kids got larger. The tolerant, generous, dedicated woman who loves me went to the meeting for the new food co-op, and she introduced the clothesline I put in last week to its first set of fresh laundry. She sent me a picture of the sun shining on our lives.

Of all the things I learned in San Francisco, the one that applies here is that blogging differs from writing, which I’ve been doing all along. Blogging demands more, and writing is just the centerpiece to a world of commenting, flickring, twittering, emailing…what we call building virtual community.

I’ve found incredible people in that community (see partial list at left). And thank you all who are reading this for being part of it, and for your indulgence. But it also turns out that I live in a community. It’s made up of people I like and don’t like, resemble and don’t resemble, agree and disagree with, and whom I can look in the eye and argue with at a meeting, but keep it civil because later I’ll run into them at the convenience store. I haven’t been engaging my community properly, either.

At the BlogHer conference last weekend, there was a panel on following your passion in which everyone agreed that the lamest Internet thing you could do was to raise up your fist and walk off the blogging stage with a grand, gestural post. Eye roll. So I'm not doing that; I don't swear to be gone for all time. My five year old — who found his first loose tooth tonight — says things like "forever." I don't.

Ahhhh, who am I kidding? The grand gesture ROCKS. Anyone needs me, I'll be tending the garden.

•

Moving the Goats

The bait: BBQ at our friends' house. The switch: "Can you help us move the goats?"

I've mentioned these friends before. They live in a large house a couple of towns away, the sort of voluminous newly-built home on a grand scale that has frequently been the subject of derision in this space, but which in their hands feels truly homey. Although the woman of the house calls it the "Plastic Palace," it's been the site of some lovely small gatherings and warm conversation. And they have a freezer full of venison donated by their oil guy. And hell, the man of the house is a Brit, the good kind--he even gets to wear a funny wig and a black robe, like, officially--and they have a kid named after a working man's folk hero, while the lady of the house is worldly and writes for a travel blog and if these two want a McMansion well then let 'em have it.

Another thing you can't argue with is the way they engage with the large meadow that surrounds it. They borrowed goats from a farm up the road.

As we drove up the long dirt driveway across this long expanse of meadow, we noticed that the portable paddock had been moved around to one of the overgrown areas in front of the house. No camera, of course, but the juxtaposition of the two goats (one black, one white), the chest-high weeds, the thick metal tubing of the fence, and the stately home with its Palladian windows and stone facing was quite something.

We entered and had our white wine, natch, and chatted about this and that, and admired the rosemary-covered chickens roasting on the rotisserie on the deck, then our friend casually said that the farmer had called and asked them to rotate the livestock. In other words, pick up the paddock sections and move them to an uneaten portion of the meadow and get the goats back inside.

Naturally the males of the group -- the risk management consultant, the marketing professional, the architect, the college student -- began ritual primate displays and paraded outside (after another fortifying Sauvignon Blanc) to show these beasts who was boss.

It took a humbling half hour, not so much to move the fence sections, but to persuade Mushroom, the more capricious of the two goats, to get back into the pen once we'd moved it. Lured by white bread, the much more tame Seven had wandered in directly. No, the funny bit was each of us trying in turn to get Mushroom's attention or herd Mushroom or persuade Mushroom to go to her home. Things goats don't respond to: clicking sounds, claps, whistles, kissing noises, their name, injunctions to "come on" delivered while slapping both thighs and bending forward. Walking toward a recalcitrant goat may cause a rearing, snorting, and suggestive horn-flinging in the direction of the walker, who, if he is a white-collar professional wearing a polo shirt, will step back in some confusion and utter a single "I say!"

We finally hit on the plan of opening the section of the pen nearest Mushroom really wide, and she walked in.

That morning at the organic farm I'd been talking to one of the local agitators, a man who refurbishes old houses and turns them into sustainable businesses, who railed against one village's unwillingness to envision a future that didn't depend entirely on oil; a self-sufficient future, with local jobs, local food sources, local culture, local commerce. We talked up over and around it for a while then said seeya, and later that evening I found myself moving a goat pen in front of a McMansion with my educated, citified, worldly friends before stepping inside to a delicious dinner and highbrow conversation.

If we're lucky and we plan right, moving the goats is the future. I certainly hope it -- or something like it -- is in my future. Because many of the alternatives are a lot worse.

•

I've mentioned these friends before. They live in a large house a couple of towns away, the sort of voluminous newly-built home on a grand scale that has frequently been the subject of derision in this space, but which in their hands feels truly homey. Although the woman of the house calls it the "Plastic Palace," it's been the site of some lovely small gatherings and warm conversation. And they have a freezer full of venison donated by their oil guy. And hell, the man of the house is a Brit, the good kind--he even gets to wear a funny wig and a black robe, like, officially--and they have a kid named after a working man's folk hero, while the lady of the house is worldly and writes for a travel blog and if these two want a McMansion well then let 'em have it.

Another thing you can't argue with is the way they engage with the large meadow that surrounds it. They borrowed goats from a farm up the road.

As we drove up the long dirt driveway across this long expanse of meadow, we noticed that the portable paddock had been moved around to one of the overgrown areas in front of the house. No camera, of course, but the juxtaposition of the two goats (one black, one white), the chest-high weeds, the thick metal tubing of the fence, and the stately home with its Palladian windows and stone facing was quite something.

We entered and had our white wine, natch, and chatted about this and that, and admired the rosemary-covered chickens roasting on the rotisserie on the deck, then our friend casually said that the farmer had called and asked them to rotate the livestock. In other words, pick up the paddock sections and move them to an uneaten portion of the meadow and get the goats back inside.

Naturally the males of the group -- the risk management consultant, the marketing professional, the architect, the college student -- began ritual primate displays and paraded outside (after another fortifying Sauvignon Blanc) to show these beasts who was boss.

It took a humbling half hour, not so much to move the fence sections, but to persuade Mushroom, the more capricious of the two goats, to get back into the pen once we'd moved it. Lured by white bread, the much more tame Seven had wandered in directly. No, the funny bit was each of us trying in turn to get Mushroom's attention or herd Mushroom or persuade Mushroom to go to her home. Things goats don't respond to: clicking sounds, claps, whistles, kissing noises, their name, injunctions to "come on" delivered while slapping both thighs and bending forward. Walking toward a recalcitrant goat may cause a rearing, snorting, and suggestive horn-flinging in the direction of the walker, who, if he is a white-collar professional wearing a polo shirt, will step back in some confusion and utter a single "I say!"

We finally hit on the plan of opening the section of the pen nearest Mushroom really wide, and she walked in.

That morning at the organic farm I'd been talking to one of the local agitators, a man who refurbishes old houses and turns them into sustainable businesses, who railed against one village's unwillingness to envision a future that didn't depend entirely on oil; a self-sufficient future, with local jobs, local food sources, local culture, local commerce. We talked up over and around it for a while then said seeya, and later that evening I found myself moving a goat pen in front of a McMansion with my educated, citified, worldly friends before stepping inside to a delicious dinner and highbrow conversation.

If we're lucky and we plan right, moving the goats is the future. I certainly hope it -- or something like it -- is in my future. Because many of the alternatives are a lot worse.

•

The insane root/That takes the reason prisoner

Encounters with the Wildlife

I.

There's a screen in the upstairs bathroom window, but there are these gnats that have evolved to be small enough to fit through its apertures because they derive some unexplained biological benefit from flitting around on the ceiling, just above the wall sconce, until they die and fall into it. There is a local legend that every time the sconce fills up with the carcasses of dead gnats, a doughty Viking warrior who long ago lost an ill-advised bar bet comes back from the dead, trudges into the house and up the stairs, tears the sconce from the wall and drains it in a single hearty draught, burps, places the sconce gently on the edge of the sink, and calls his friend Larry's brother-in-law who "[can] totally rewire shit."

II.

The day before I caught the pike, my brother and I were fishing for pickerel from the canoe. Nearby, the lilypads began moving of their own accord, spreading apart as though making way for an invisible bride walking upon the water. As I crossed myself and shook my charm bracelet, my brother looked UNDER that water and spotted the snapping turtle. We both peered at it in the shallows, remarking that its mighty legs alone would serve as hams, while its garbage-can-lid-sized shell would make an ideal garbage can lid. So imagine a garbage can lid balanced on four hams, but it's, like, swimming. I wish I had a picture, but the snapping turtle consumed the very idea of my camera before I even thought it -- which is just how big that turtle was.

III.

Next day, I caught my first northern pike. You know, you're just sitting there dangling bits of colored plastic decorated with needle-sharp bent metal barbs into the water and a fucking fish bites your shit. When animals attack, right?

IV.

Various deer. Constantly.

V.

Mouse in the grill. Covered that.

VI.

Some roadkill.

VII.

Oh, right, this morning. They've repaved the parking lot at the office park where I work, and this morning there was a security guard on the hot tar, standing watch over a "snapping turtle" -- I have to put it in quotes because of that one I saw in the Adirondacks last week -- as it crossed from god-knows-where to wherever-the-hell.

VIII.

I was tucking my son in tonight when I saw a yellowjacket sitting on his window sill, slowly undulating one antenna. I picked up North Dakota, gathered my courage, and thwapped it. It crackled like evil rice krispies. I still don't know if it was actually already dead, or paralyzed or something, but still, the bravery.

Just then I heard the heavy tread of a Viking on the stairs.

•

There's a screen in the upstairs bathroom window, but there are these gnats that have evolved to be small enough to fit through its apertures because they derive some unexplained biological benefit from flitting around on the ceiling, just above the wall sconce, until they die and fall into it. There is a local legend that every time the sconce fills up with the carcasses of dead gnats, a doughty Viking warrior who long ago lost an ill-advised bar bet comes back from the dead, trudges into the house and up the stairs, tears the sconce from the wall and drains it in a single hearty draught, burps, places the sconce gently on the edge of the sink, and calls his friend Larry's brother-in-law who "[can] totally rewire shit."

II.

The day before I caught the pike, my brother and I were fishing for pickerel from the canoe. Nearby, the lilypads began moving of their own accord, spreading apart as though making way for an invisible bride walking upon the water. As I crossed myself and shook my charm bracelet, my brother looked UNDER that water and spotted the snapping turtle. We both peered at it in the shallows, remarking that its mighty legs alone would serve as hams, while its garbage-can-lid-sized shell would make an ideal garbage can lid. So imagine a garbage can lid balanced on four hams, but it's, like, swimming. I wish I had a picture, but the snapping turtle consumed the very idea of my camera before I even thought it -- which is just how big that turtle was.

III.

Next day, I caught my first northern pike. You know, you're just sitting there dangling bits of colored plastic decorated with needle-sharp bent metal barbs into the water and a fucking fish bites your shit. When animals attack, right?

IV.

Various deer. Constantly.

V.

Mouse in the grill. Covered that.

VI.

Some roadkill.

VII.

Oh, right, this morning. They've repaved the parking lot at the office park where I work, and this morning there was a security guard on the hot tar, standing watch over a "snapping turtle" -- I have to put it in quotes because of that one I saw in the Adirondacks last week -- as it crossed from god-knows-where to wherever-the-hell.

VIII.

I was tucking my son in tonight when I saw a yellowjacket sitting on his window sill, slowly undulating one antenna. I picked up North Dakota, gathered my courage, and thwapped it. It crackled like evil rice krispies. I still don't know if it was actually already dead, or paralyzed or something, but still, the bravery.

Just then I heard the heavy tread of a Viking on the stairs.

•

Making Do

The Walking Fool

In 2001, my friend Mark started walking from New Jersey to California. Several months later, in Sioux Falls, SD, he decided he was finished with the heat and mosquitoes, and came back to New York.

This March he set out again. I got a call from him tonight outside of Bancroft, Nebraska, and he wanted you all to know he was doing very well, but wouldn't mind a cool drink of water from friendly strangers now and then.

Please to visit his site and read his blog, then tell your Nebraskan friends to keep a friendly eye out, and wish him well. Someday you'll get to see the full documentary, the quality of which can be deduced from the trailer he made for a filmed version of his first trip.

•

This March he set out again. I got a call from him tonight outside of Bancroft, Nebraska, and he wanted you all to know he was doing very well, but wouldn't mind a cool drink of water from friendly strangers now and then.

Please to visit his site and read his blog, then tell your Nebraskan friends to keep a friendly eye out, and wish him well. Someday you'll get to see the full documentary, the quality of which can be deduced from the trailer he made for a filmed version of his first trip.

•